The Sunshine Coast’s architectural landscape reflects over a century of adaptation—first to environment, then to population growth, tourism, and more recently, sustainability. From early settler structures to contemporary civic buildings, architecture here has always been closely tied to lifestyle, climate, and community needs.

Early Settlement and Colonial Architecture

Before European arrival, the Sunshine Coast was home to the Kabi Kabi (Gubbi Gubbi) and Jinibara peoples, whose connection to land shaped how they lived and moved across the region. While their architectural legacy wasn’t based on permanent structures, it influenced how later generations thought about working with the land rather than against it.

When colonial settlement began in the 1800s, early buildings were designed for practicality. Timber was used extensively, thanks to its availability and suitability for the climate. Homes like Koongalba in Yandina (built in 1894) are good examples of this era—timber-framed, elevated on stumps, with wide verandahs for airflow and shade.

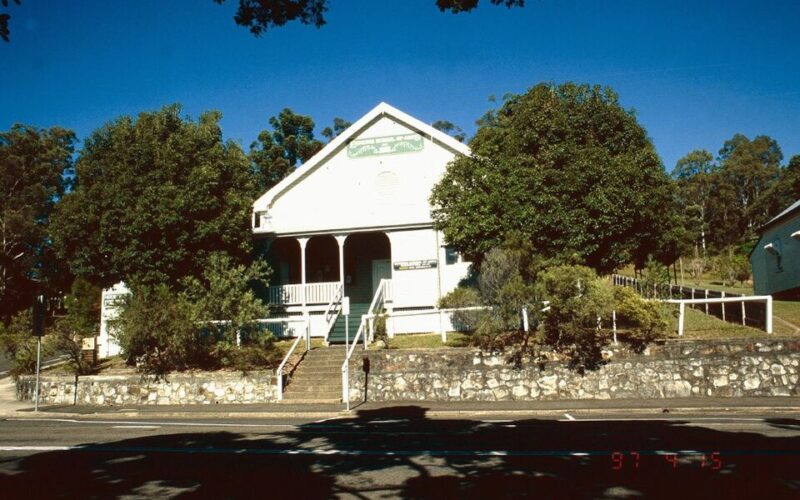

Public buildings followed a similar logic, often blending classical design influences with local materials. The Eumundi School of Arts (1912) is a heritage-listed examples that reflect the values of early 20th-century civic architecture: modest scale, symmetry, and durability.

Mid-Century Growth and the Rise of Coastal Identity

By the 1950s, tourism was becoming central to the Sunshine Coast economy. Architecture adapted accordingly. Homes and accommodation moved away from the formality of earlier decades, favouring open layouts, larger windows, and materials suited for relaxed, beachside living. This period introduced the idea of architecture as a reflection of lifestyle, not just function.

The 1970s marked a turning point with larger developments like the Maroochy Sands Holiday Inn—one of the first high-rise buildings in the region. It represented a move toward verticality and a more commercialised coastline, setting the tone for later tourism-led construction.

But not everyone followed that path. Architect Maurice Hurst, working primarily in Noosa, pushed for a more restrained approach—what would come to be known as the “Noosa Style.” His work prioritised low-scale, timber-based construction that sat lightly on the landscape. His influence remains strong in local planning decisions and design codes today.

Regional Architects and the Local Movement

From the late 1980s onward, a group of architects based on the Sunshine Coast began to shape a distinct regional architectural language. Figures like Gabriel Poole, John Mainwaring, and Lindsay and Kerry Clare emphasised climate-responsive design: buildings that used passive cooling, local materials, and flexible spaces suited to the subtropics.

Their work received national attention and became a benchmark for regional design in Australia. The homes they created weren’t showy—they were thoughtful, site-specific, and designed to last.

Heritage, Preservation and Adaptive Reuse

While architectural innovation has been a strong feature of recent decades, preservation has become equally important. Significant heritage structures—like Bankfoot House near the Glass House Mountains, Buderim House, and the Caloundra Lighthouses—have been conserved to ensure the region’s history isn’t lost to new development.

At the same time, adaptive reuse has become a practical way to bridge past and present. The Imperial Hotel in Eumundi, for example, has been modernised while retaining its original structure and character. Similarly, the once-dormant Big Pineapple has been reactivated as a cultural and tourism precinct, showing that heritage doesn’t always mean static preservation.

Contemporary Direction

Recent projects like the Sunshine Coast City Hall, completed in 2023, show how local architecture continues to evolve. Designed with a focus on sustainability, transparency, and public use, it’s part of a new generation of civic buildings that reflect both local values and global concerns.

Residential architecture is also changing. Award-winning homes like Family Tree House show how smaller, site-sensitive architecture continues to define the region—offering alternatives to generic development and prioritising landscape, climate, and material honesty.

The Sunshine Coast’s architecture doesn’t follow a single style, but a clear thread runs through its history: buildings here respond to their environment. Whether shaped by necessity, climate, or community values, architecture on the Coast has always been about living well in a specific place. The challenge now is to maintain that connection as the region grows.